Rewrites: A Memoir

by Neil Simon

(1998)

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

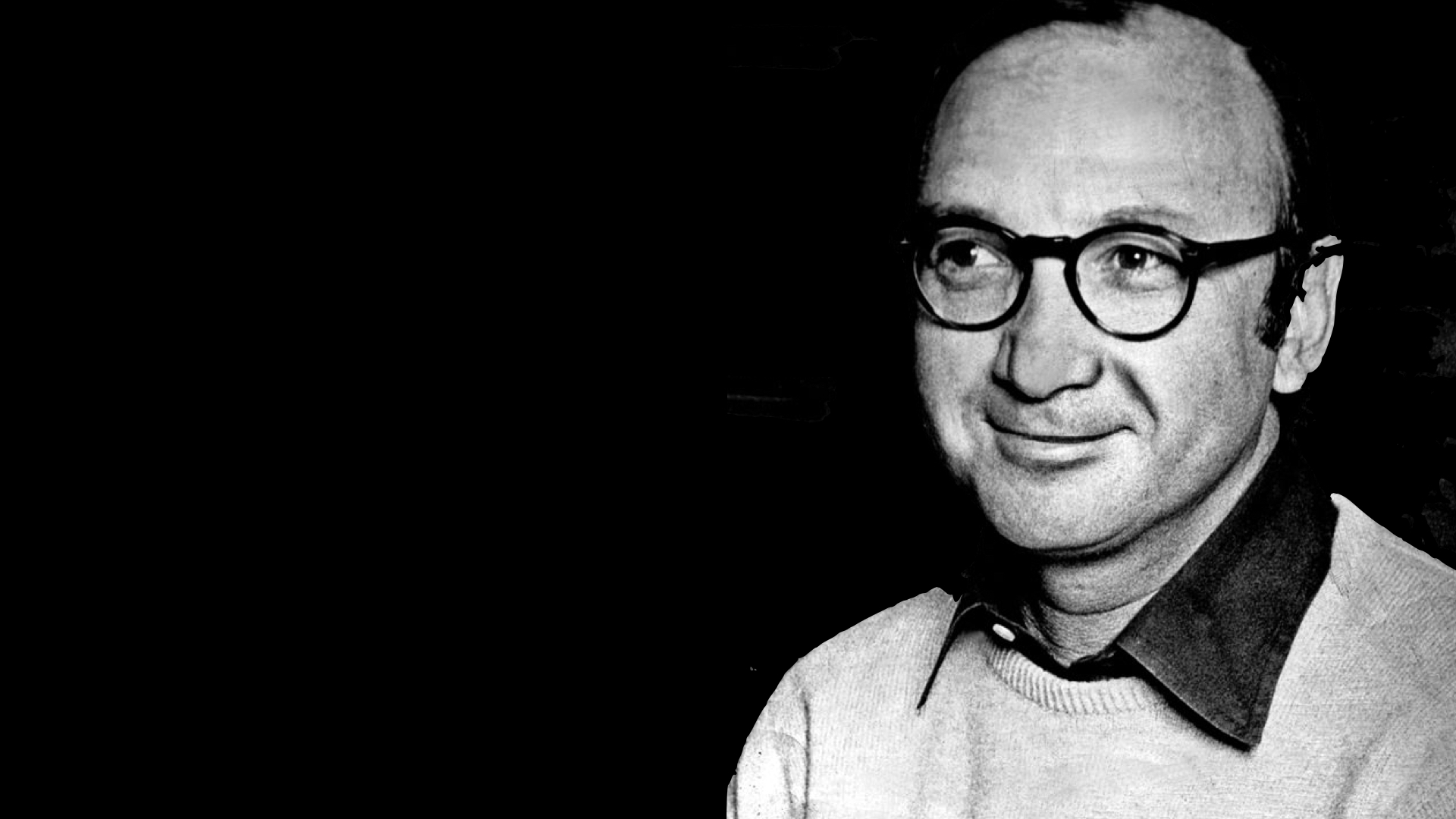

Neil Simon is both a playwright and screenwriter. He is responsible for epic comic creations such as The Odd Couple, Barefoot in the Park, and The Prisoner of 2nd Avenue. His book, Rewrites: A Memoir, deals with his early years, and is an inspiring resource for any new or insecure writer – which, compared to Simon, is all of us.

In Rewrites Simon observes: “A playwright has one advantage over screenwriters. An audience will tell you immediately what’s wrong, and you can go home and fix it … The more live performances of my play, the more chances I get at improving it.” In the absence of a live audience, scriptwriters require feedback of a different kind. The notes we get from various readers are a process of ‘hearing’ what’s wrong with our screenplay prior to production. Simon’s book provides some great insight into how to do that.

Simon’s early career was as a staff writer on the Caesar’s Hour – along with Carl Reiner, Larry Gelbart, Mel Brooks and Sid Caesar. Isn’t that the greatest line up of 20th century comedy scriptwriters? Among the early disciplines he gained on this popular live show, was the vital lesson of editing: “What you take out is as important as what you leave in.”

His big break from television came from the most unlikely quarter. A freelance job writing for Jerry Lewis ended sooner than he anticipated; “Jerry Lewis sat and read them [the pages of his script] in stony silence. Not a sound, not a peep, not a smile, not a chuckle. “I love ’em. Hysterical! We’re finished. Wasn’t that easy?”

“But you never laughed once,”

“I’ll laugh when we do it. I’m not funny when I read.”

“So what about rewrites?”

“We’ll fix it in rehearsal.”

This freed up five weeks, and Simon used the time to start writing the first draft of his first play, Come Blow Your Horn. It eventually took him a year to finish, and two and a half years to rewrite. “I did twenty-two complete versions, starting on page one and finishing on page 125 every time, and almost never did I repeat myself.”

From this frankly robust writing experience, Simon passes on a few valuable lessons for how to assess your own work: “Putting a play, or even one act, into a drawer and not looking at it for at least a few weeks makes wondrous things happen. Its faults suddenly become very clear.”

He suggests showing your work as soon as possible. “Your best bet, I’ve always found, is to show your work to just two people. One is the most honest person you know, the other is the smartest person you know.”

The early readers of his work were: his wife and muse Joan, and then friends in the business; and finally the Broadway producers he was trying to tempt.

“Mediocre and bad writing is easy to spot, not only during the heavy night at the theatre, but in your own work, and if you do it often enough you begin to recognize the signals. You can never say to yourself, ‘I think there’s a problem here, but maybe I’m wrong. Maybe they’ll like it.’ They won’t.”

Neil Simon from “Rewrites: A Memoir”

Over the process of his 22 drafts, Simon learned about the importance of structure, character and tone, but it wasn’t until the play was performed, that he discovered, “Real people are the fairest audience you can get, because they have no emotional interest in the event they are about to witness.”

Mike Nichols was the original Broadway Director for The Odd Couple. They realized during the read through that the third act wasn’t working. Nicols advised Simon to: “‘Stop trying to fix what you have. Throw it out of your mind. It doesn’t exist anymore. Now go back and write it.’ When I did, I felt liberated from the obligation to fix something that wasn’t working. Now I could create something that didn’t have a negative history.”

This was an epiphany for Simon; one which liberated him to write more energetically, but I need to think about this for a moment. Throwing out everything and starting again is a bold move, but no-one cheers when Ernest Hemingway loses his manuscript and has to rewrite it. On the other hand, cobbling together two mismatched ideas can be a pain. I wonder if this is general advice, or only for certain writers, or perhaps certain crises. Simon doesn’t like to ‘plot’ his stories, and he mainly writes comedies of manners. Furthermore, he has a natural ear for dialogue – meaning this advice may suit his style of ‘plein air’ writing… but, well, it makes me so very squeamish – I might just have to try it on my next crisis.

Simon is gracious enough to detail this particular third act problem through numerous drafts; “There’s a point that comes in which you think there’s nothing you can put down that’s any good, and your own judgment isn’t worth the paper you’re not writing on. People think that’s what writer’s block is. They assume you can’t think of a single thing. Not true. You can think of hundreds of things. You just don’t like any of them. And what you like, you don’t trust.”

This particular problem (with the third act of The Odd Couple) wasn’t resolved until an out of town critic observed. “I missed the Pigeon Sisters. They were so darned funny and I wondered why you didn’t bring them back.”

Simon and Nichols immediately reinstated them – but it still didn’t work, and Simon needed to keep re-writing, until neither knew how it would be received. Nichols quipped at one point, “Write something bad, maybe that will work.”

Finally they got the balance right and the audience: “even laughed on lines I didn’t think were terribly funny. The characters were now believable in a manner that pleased and amused the audience, that made them empathetic to the foibles of these people we had just spent an evening with. In the ensuing weeks, I was able to replace the weaker lines with better ones, but it was the characters and the story’s development that pleased the audience so much.

Given his willingness to write and rewrite, it becomes evident that knowing when to stop is also important. Plainly, this is a delicate art in itself. Simon tells the story of an art teacher with a third-grade class who obtained wonderful results from her students. The parents, amazed, wanted to know how she could make their eight- and nine-year-old better painters than the previous teacher. The woman explained, ‘I just know when to take it away from them.’

Rewrites: A Memoir

by Neil Simon

(1998)

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 0684835622

ISBN-13: 978-0684835624

ISBN: B002ASURCQ

It’s more than bold, it’s staggeringly brave, like starting in the first place. It takes guts to throw away precious, hard-fought words. Words that maybe only came out under great pressure. But perhaps Simon was not suggesting chucking the lot. When he throws the words out, he still keeps in mind his story, characters, setting etc.

Maybe it’s just easier to start again on a bank page with the same general destination in mind than to try to fix something irreparably broken. If so, I can see how that might be liberating. Scary as hell, but still liberating.

Love what you’re doing here, Sheri. There’s brain food here for all kinds of writers.